Tennis elbow, also called lateral epicondylitis, is an inflammation of the lateral (outside) bony protuberance at the elbow. It is at this protuberance that the tendon of the long muscles of the hand, wrist and forearm attach to the bone. As the muscles repeatedly and forcefully contract, they pull on the bone, causing inflammation. The trauma is irritating when working the muscles in an awkward position with poor leverage like hitting a backhand in tennis.

It is not unusual for a patient to come to my office with severe pain on the outside of their elbow. Especially, after intensifying their tennis workouts or changing the racquet string tension. Others come to me with pain on the inside of the elbow (“golfer’s elbow”) from wrist action that advanced golfer’s use at impact. However, this problem is not only for tennis players and golfers. Laborers working with wrenches or screwdrivers with an awkward or extended arm can also develop tennis elbow. Others who are vulnerable are: those working for hours at a computer using a mouse as well as those working hard maintaining their lawns and gardens.

In a more chronic problem, lateral elbow pain may arise by a degenerative condition of the tendon fibers on the bony prominence at the lateral elbow. Sporadic scar tissue forms from a poor attempt by the body to overcompensate and heal without eliminating the cause.

While symptoms may vary, pain on the outside of the elbow is almost universal. Patients also report severe burning pain that begins slowly and worsens over time when lifting, gripping or using fingers repetitively. In more severe cases, pain can radiate down the forearm.

Conservative treatment is almost always the first option and is successful in 85-90 percent of patients with tennis elbow. Your physician may prescribe anti-inflammatory medication (over the counter or prescribed). Physical/Occupational therapy, rest, ice, and a tennis elbow brace to protect and rest may be advised. Ergonomic changes in equipment, tools, technique and work-station may be necessary. Improvement should occur in 4-6 weeks. If not, a corticosteroid injection may be needed to apply the medication directly to the inflamed area. Physical therapy, range of motion, and stretching exercises may be necessary prior to a gradual return to activity. Deep friction massage can assist healing.

Exercises performed in a particular manner to isometrically hold and eccentrically lengthen the muscle with contraction.

New Conservative Treatment: Platelet-Rich-Plasma (PRP) is a new treatment for the conservative management of degenerated soft tissues that has recently received great media attention. In great part, due to its success in several high profile athletes. According to the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons,(JAAOS), platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is autologous (self-donated) blood with an above normal concentration of platelets. Normal blood contains both red and white blood cells, platelets and plasma. Platelets promote the production and revitalization of connective tissue by way of various growth factors on both a chemical and cellular level.

The actual PRP injection requires the patient to donate a small amount of their own blood. The blood is placed into a centrifuge (a machine that spins the blood at a high velocity to separate the different components of blood such as plasma, white and red blood cells), for approximately 15 minutes. Once separated, the physician draws the platelet-rich plasma to be injected directly into the damaged tissue. In theory, the high concentration of platelets, with its inherent ability to stimulate growth and regeneration of connective tissue, will promote and expedite healing.

Surgery for tennis elbow is only considered in patients with severe pain for longer than 6 months without improvement from conservative treatment. One surgical technique involves removing the degenerated portion of the tendon and reattaching the healthy tendon to bone. Recently, arthroscopic surgery developed to perform this technique. However, research does not support the value of one over the other at this point. Physical/occupational therapy is used after surgery. Return to work or athletics may require 4-6 months. More recently, a surgical technique using ultrasound to guide a needle to debride (clean) the area of scar tissue has been developed. If eligible for this procedure, the time required for healing, rehabilitation and return to activity is much shorter.

If you feel you suffer from tennis elbow, ask your family physician which of these treatment options are best for you.

Visit your doctor regularly and listen to your body.

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopaedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

As most sports enthusiasts know, Aaron Rodgers, former Green Bay Packer quarterback and recent New York Jets QB (for just over a minute and half) suffered a season ending injury when he tore his Achilles tendon in the first game of the 2023/24 NFL season. Since then, I have been answering many questions from patients and sports fans about the nature of the Achilles Tendon rupture injury, recovery, and how to prevent it.

As the days continue to get shorter and temperatures begin a slow steady decline, athletes and exercise enthusiasts will work harder to warm-up and exercise during the winter months. A little caution and preparation are in order to avoid muscle/tendon strain, or worse yet, muscle/tendon tears, especially Achilles Tendon rupture. The Achilles tendon is one of the more common tendons torn.

This is the second of two columns on Achilles tendon rupture. Last week, I discussed the definition, sign and symptoms of the problem. This week will present examination, treatment and outcomes.

A thorough history and physical exam is the first and best method to assess the extent of the injury and determine accurate diagnosis. While a complete tear is relatively easy to determine, a partial or incomplete tear is less clear. Ultrasound and MRI are valuable tests in these cases. X-rays are not usually used and will not show tendon damage.

Consultation with an orthopedic or podiatric surgeon will determine the best treatment option for you. When conservative measures fail and for tendons completely torn, surgical intervention is usually considered to be the best option with a lower incidence of re-rupture. Surgery involves reattaching the two torn ends. In some instances, a graft using another tendon is required. A cast or walking boot is used post-operatively for 6-8 weeks followed by physical therapy.

Most people return to close to normal activity with proper management. In the competitive athlete or very active individual, surgery offers the best outcome for those with significant or complete tears, to withstand the rigors of sports. Also, an aggressive rehabilitation program will expedite the process and improve the outcome. Walking with full weight on the leg after surgery usually begins at 6 -8 weeks and often requires a heel lift to protect the tendon. Advanced exercises often begin at 12 weeks and running and jumping 5-6 months. While a small bump remains on the tendon at the site of surgery, the tendon is well healed at 6 months and re-injury does not usually occur.

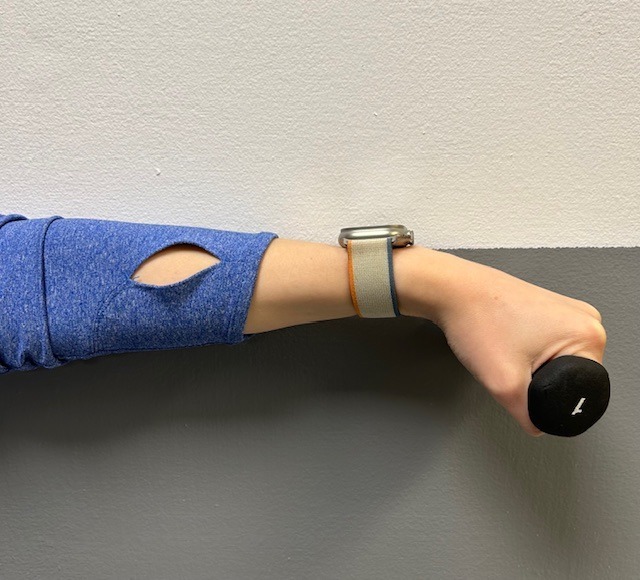

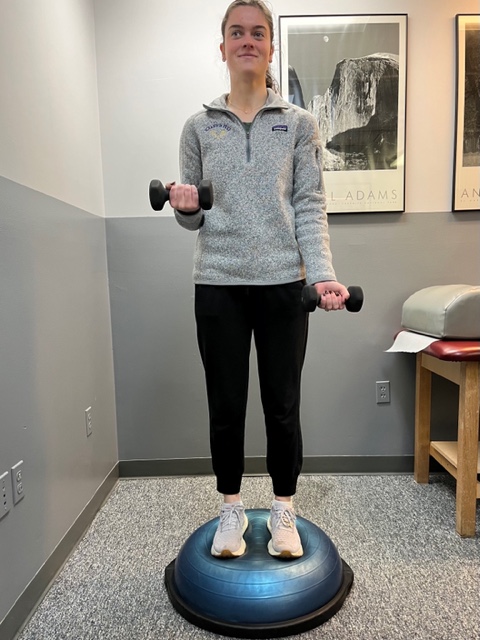

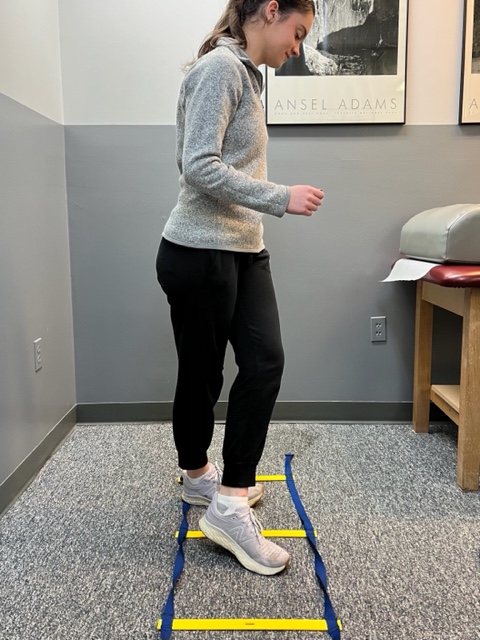

Prevention of muscle and tendon tears is critical for healthy longevity in sports and activities. In addition to the Achilles tendon, the tendons of the quadriceps (knee) and rotator cuff (shoulder) are also vulnerable. A comprehensive prevention program includes: gradual introduction to new activities, good overall conditioning, sport specific training, pre-stretch warm-up, stretch, strengthening, proper shoes, clothing, and equipment for the sport and conditions. Also, utilizing interval training, eccentric exercise (lowering body weight slowly against gravity – Photo 1) and proprioceptive and agility drills are essential (Photos 2 & 3).

In PHOTO 1a & 1b: Eccentric Lowering and Lengthening: for the Achillies tendon during exercise. Beginning on the ball of both feet (1a), bend the strong knee to shift the weight onto the weak leg (1b). Slowly lowering the ankle/heel to the ground over 5-6 seconds. Repeat.

In PHOTO 2: Proprioceptive Training: for the Achillies tendon. Standing on a Bosu Ball while exercising the upper body (for example, biceps curls, shrugs, rows, lats) while maintaining balance on the ball.

PHOTO 3: Agility Drills: for the Achilles tendon involves stepping through a “gait ladder” in various patterns and at various speeds.

MODEL: Kerry McGrath, student physical therapy aide at Mackarey Physical Therapy

Sources: MayoClinic.com;Christopher C Nannini, MD, Northwest Medical Center;Scott H Plantz, MD, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopedic and sports physical therapy. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at GCSOM. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

HEALTH AND EXERCISE FORUM

By: Dr. Paul J. Mackarey

This column is a monthly feature of “Health & Exercise Forum” in association with the students and faculty of Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine (formerly The Commonwealth Medical College).

Guest Columnist: Kevin Perry, MD

“Should I use heat or ice?” Several years ago, while working as a third year medical student at TCMC on orthopedic rotation, I was surprised to find that this is one of the most common questions asked by weekend warriors trying to relieve shoulder pain after playing tennis for the first time in 6 months. Now, as an orthopedic resident, the frequency of this inquiry has not changed. Trying to decide whether to use ice or heat to make it feel better and heal faster may not be so easy. Unfortunately, there is confusion, even among medical professionals, about the appropriate times to use heat or cold. However, if we review the basic science on this subject, there are some valuable guidelines to consider.

The Science

When an injury is sustained, such as a sprained ankle, chemical signals are released in the area of the injury, which increases blood supply to the damaged tissues to allow appropriate cells to repair the damage. This response is evident by the principle signs and symptoms of inflammation including heat, redness, swelling, pain, and loss of function. This reaction makes sense because anytime tissues are injured; the body is responsible to protect the site until repair can occur. To protect the injured site, the body causes swelling and pain to prevent excessive movement or overuse which will lead to further injury. With the site of injury protected, the appropriate cells are able to lay down new tissue to repair the damage. As tissues heal, a web of connective tissue pulls the damaged tissues back together and holds them in place while new tissue is formed. Once the tissue is completely repaired, the blood flow returns to normal and fluid drains from the site of injury allowing restoration of motion and function. However, the new tissue is fragile and unorganized and often sticks together leaving tightness and weakness. After repeated use, the new tissue adapts to the stress placed upon it and becomes functional.

The Application

When grounded in science, the use of heat or cold can be used to expedite the healing process. While inflammation is crucial to the repair of injured tissue, the response can be exaggerated and last longer than necessary. Therefore, ice and heat can be used to modify the bodies’ inflammatory response and help us return to activity sooner.

How Cold Works

Ice causes blood vessels to narrow and nerves to slow down. When ice is applied to tissue, the body responds by decreasing blood flow to the area to preserve the core body temperature. Also, as nerves cool down, the signals they send slow down and become less frequent, so the pain signals they send to your brain become less intense. Thus, we can use ice to decrease blood flow to inflamed tissue which will reduce swelling and decrease pain. Ice is ideally used immediately following most injuries to control pain and swelling.

How Heat Works

Heat causes your blood vessels to open and increase blood flow to tissues. When heat is applied, blood flow and tissue temperature are increased and tight tissues relax and are better able to glide across one another. However, when applied too early in the healing process, heat, by increasing blood flow, can increase swelling and pain. Heat is ideally used after an injury has healed and there is residual tightness or protective muscle spasms.

Now that we know how ice and heat work in conjunction with the inflammatory process we can easily understand when to use each one. Ice is best used following an acute injury. For example, ice is effective day one through three following an ankle sprain, or until swelling is controlled. Anytime the principle signs and symptoms of inflammation are present, ice is the appropriate treatment of choice. Regardless of when the injury occurred, if there is swelling and pain, ice is the appropriate treatment. Heat should be used when there is tightness and stiffness and no signs of acute inflammation. For example, week two of three, following an ankle sprain if stiffness persists and swelling is controlled.

How To…

Apply ice using a bag of ice and water, ice pack, or bag of frozen vegetables wrapped in a wet towel. Cover the injured and swollen area and if possible elevate the iced area above the level of your heart. You should apply ice for a maximum of 20 minutes and rest at least one hour between icing sessions so as not to cause harm. Never apply ice directly to skin and never fall asleep while icing.

Apply heat with a heating pad covered in a few towels or warm a bag of rice in a microwave. Cover in a towel and place the heat on the affected area for a maximum of 20 minutes and rest at least one hour between heating sessions. Never apply heat over skin that you cannot feel (numbness or loss of sensation) or on open wounds in the skin. Also, do not lie directly on the heating source and don’t fall asleep while using heat to avoid burns.

Hopefully this information is helpful in dispelling some of the confusion regarding when to use ice or heat. As you can see there is no “golden rule” or “72-hour rule” for advising when to use ice or heat. But if you stick to the principles discussed in this article, you should be treating your aches and pains appropriately. This has been a simplified explanation of a complex topic and if you have any further questions, please ask a medical professional.

Top Reasons for use of Ice (Cryotherapy):

Top Reasons for use of Heat (Thermotherapy):

Kevin Perry, MD graduated from The Commonwealth Medical College (GCSOM) in 2015. He is a resident in Orthopaedic Surgery at LSU Health Science Center Shreveport and will be moving back to Pennsylvania next month to pursuit a fellowship in orthopedic trauma at Penn State Health Milton S Hershey Medical Center. His special interests include pelvis and acetabulum trauma, complex periarticular fractures, malunions, nonunions, and deformity correction. Dr Perry completed his undergraduate education at Loyola University Maryland and graduate degree (doctor of physical therapy) at the University of Scranton.

Read all of Dr. Mackarey's articles in the Health and Exercise Forum at our website: https://mackareyphysicaltherapy.com/forum/

Read “Health & Exercise Forum” – Every Monday. This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at GCSOM.