At least once a week, a patient jokingly asks if they can get a “lube job” to loosen up their stiff knee joint. I respond by providing them with information about osteoarthritis and viscosupplementation, a conservative treatment administered by injection and approved by the FDA for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is also known as degenerative arthritis. It is the most common form of arthritis in the knee. OA is usually a gradual, slow and progressive process of “wear and tear” to the cartilage in the knee joint which eventually wears down to the bony joint surface. It is most often found in middle-aged and older people and in weight bearing joints such as the hip, knee and ankle. Symptoms include: pain, swelling, stiffness, weakness and loss of function.

Your family physician will examine your knee to determine if you have arthritis. In more advanced cases you may be referred to an orthopedic surgeon or rheumatologist for further examination and treatment. It will then be determined if you are a candidate for viscosupplementation. While this procedure is the most commonly used in the knee, it has also been used for osteoarthritis in the hip, shoulder and ankle.

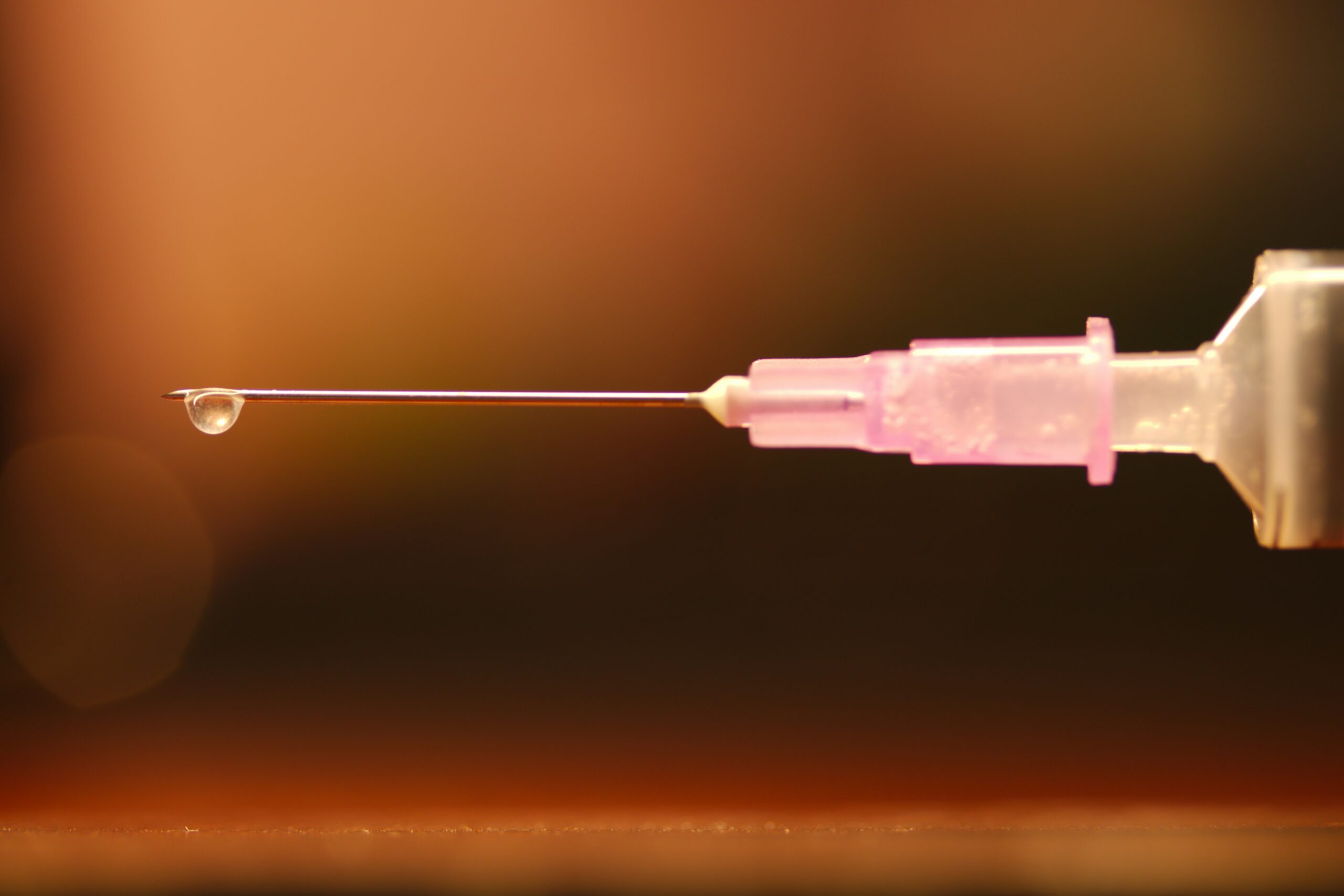

Viscosupplementation is a procedure, usually performed by an orthopedic surgeon or rheumatologist, in which medication injected into the knee joint acts like a lubricant.

The medication is hyaluronic acid is a natural substance that normally lubricates the knee. This natural lubricant allows the knee to move smoothly and absorbs shock. People with osteoarthritis have less hyaluronic acid in their knee joints. Injections of hyaluronic acid substances into the joint have been found to decrease pain, improve range of motion and function in people with osteoarthritis of the knee.

When conservative measures, such as anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, steroid injections fail to provide long lasting relief, viscosupplementation may be a viable option. Often, physical therapy and exercise are more effective following this injection to provide additional long-term benefit. Unfortunately, if conservative measures, including viscosupplementation fails, surgery, including a joint replacement may be the next alternative.

In 1997 the FDA approved viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee. Presently, there are several products on the market. One type is a natural product made from the comb of a rooster. However, if you are allergic to eggs or poultry products or feathers, you should not use the natural product. The other medication is best used for patients with allergies because it is manufactured as a synthetic product.

The long-term effects of viscosupplementation is much greater when other conservative measures are employed:

SOURCES: Genzyme Co, Sanofi-Synthelabo Inc, Seikagaku Co. and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Visit your doctor regularly and listen to your body.

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

Osteochondritis dissecans, also called OCD, is the most common cause of a loose body or fragment in the knee and is usually found in young males between the ages of ten and twenty. While this word sounds like a mouth full, breaking down its Latin derivation to its simplest terms makes it understandable: “osteo” means bone, “chondro” means cartilage, “itis” means inflammation, and “dissecans” means dissect or separate. In OCD, a flap of cartilage with a thin layer of bone separates from the end of the bone. As the flap floats loosely in the joint, it becomes inflamed, painful and disrupts the normal function of the joint.

Typically, OCD is found in the knee joint of active young men who participate in sports which involve jumping or full contact. Although less common, it is also found in other joints such as the elbow.

Often, the exact cause of OCD is unknown. For a variety of reasons, blood flow to the small segment at the end of the bone lessens and the weak tissue breaks away and becomes a source of pain in the joint. Long term, OCD can increase the risk of osteoarthritis in the involved joint.

To properly diagnose OCD a physician will consider onset, related activities, symptoms, medical history, and examine the joint involved for pain, tenderness, loss of strength and limited range of motion. Often, a referral to a specialist such as an orthopedic surgeon for further examination is necessary. Special tests specifically detect a defect in the bone or cartilage of the joint such as:

Radiograph (X-ray) may be performed to assess the bones.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) may be performed to assess bones and other soft tissues such as cartilage, ligaments, muscles and tendons.

The primary goal of treatment for OCD is to relieve pain, control swelling, and restore the complete function (strength and range of motion) of the joint. The age of the patient and severity of the injury determine the treatment methods. For example, medications assist with pain and inflammation reduction.

Young patients who are still growing have a good chance of healing with conservative treatment. Rest and physical therapy are the conservative treatments of choice. Rest entails avoiding any activity that compresses the joint such as jumping, running, twisting, squatting, etc. In some cases, using a splint, brace and crutches to protect the joint and eliminate full weight bearing, may be necessary for a few weeks. Physical therapy, either as a conservative or post operative treatment, involves restoring the range of motion with stretching exercises and improving the strength and stability of the joint through strengthening exercises. Modalities for pain and swelling such as heat, cold, electrical stimulation, ultrasound, compression devices assist with treatment depending on the age of the patient and severity of the problem.

Conservative treatment can often require 3 to 6 months to be effective. However, if it fails, arthroscopic surgery stimulates healing or reattaches the loose fragment of cartilage and bone. In some cases if the defect is small, surgery involves filling in the defect with small bundles of cartilage. In other cases, the fragment is reattached directly to the defect using a small screw or bioabsorbable device. More recently, surgeons are using the bone marrow of the patient to repair the deficit by stimulating the growth of new tissue (bone marrow stimulation).

In other cases, a plug of healthy tissue from the non-weight bearing surface of a patient's knee relocated to the defect to stimulate healing (osteochondral autograft transplantation OATS). While there are many surgical options for OCD, an orthopedic surgeon will help the patient decide the most appropriate procedure based on age, size of defect, and other factors.

While prevention is not always possible, some measures can be taken to limit risk. For example, if a child playing sports has a father and older brother who had OCD, then it would be wise to consider the following: Avoid or make modifications for sports requiring constant jumping. Cross-train for a sport to avoid daily trauma (run one day and bike the next). Also, do not play the sport all year round (basketball in the fall/winter and baseball in the spring/summer). Seek the advice from an orthopedic or sports physical therapist to learn proper strength and conditioning techniques. Learn proper biomechanics of lifting, throwing, squatting, running, jumping and landing.

Sources: Mayo Clinic

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

Several years ago, while hiking to the bottom of the Grand Canyon with my family, my wife Esther developed “canyon knee,” also known as “hiker’s knee” or in medical terms, “patellar tendonitis.” Regardless of the term, the end result was that she had severe pain in the tendon below her knee cap and was unable to walk up the trail to get out of the canyon. In addition to ice, rest, bracing, and non-steroidal anti inflammatory medications, the National Park Ranger insisted that she use two trekking poles on her ascent to the rim.

Prior to that experience, I always thought that “walking, hiking sticks or trekking poles” were for show or those in need of a walking aide. Well, I could not have been more incorrect. Needless to say, Esther made it out of the canyon safely and, with the use of our life saving trekking poles; we have lived “happily ever after!” Now, 15 years later, I rarely walk more than 5 miles without my poles.

As a result of this experience, I have been recommending walking or trekking poles to my patients. These poles are an essential part of hiking or distance walking gear, for the novice and expert alike. Specifically, for those over 50 who have degenerative arthritis and pain in their lower back, hips, knees, ankles or feet, these simple devices have been shown to improve the efficiency of the exercise and lessen the impact on the spine and lower extremities. Additionally, using poles reduces the likelihood of ankle sprains and falls during walking. Trekking poles are also a safe option for those with compromised balance. If you want to walk distances for exercise and need a little stability but don’t want the stigma of a cane, trekking poles are for you.

Early explorers, Europeans and Native Americans have been using walking sticks for centuries. More recently, in the 1968 classic hiker’s bible, “The Complete Walker,” Colin Fletcher praised his “walking staff” for its multipurpose use: for balance and assistance with walking and climbing, protection from rattlesnakes, and for use as a fishing rod. Today, these sticks are now versatile poles made from light-weight materials.

Trekking poles are made of light-weight aluminum and vary in cost and quality. But, like most things, “you get what you pay for!” These hollow tubes can telescope to fit any person and collapse to pack in luggage for travel. Better poles offer multiple removable tips for various uses, conditions and terrains. For example, abasket to prevent sinking too deeply in snow, mud or sand; a blunt rubber tip for hard surfaces like asphalt or concrete, or the pointed metal tip to grip ice or hard dirt/gravel. Better quality poles offer an ergonomic hand grip and strap and a spring system to absorb shock through your hands, wrists and arms upon impact.

The poles should be properly adjusted to fit each individual. When your hand is griping the handle the elbow should be at a 90 degree angle. Proper use is simple; just walk with a normal gait pattern of opposite arm and leg swing. For example, left leg and right arm/pole swings forward to plant while the left arm/pole remain behind with the right leg .

This pattern is reciprocated with as normal gait advances (opposite arm and leg). I have been very pleased with my moderately priced poles (Cascade Mountain Tech from Dick’s Sporting Goods ($34.99 per pole). Prices range from $19.99 to 79.95 per pole. dickssportinggoods.com; montem.com; leki.com; rei.com. However, if you travel frequently to hike the State and National Parks, you may want to purchase more expensive poles that collapse and retighten more efficiently. (montem.com; leki.com;)

Montem Trekking Poles - with close-up of easy adjustable locking clasp.

There are numerous studies to support the use of trekking poles, especially research that supports their use for health and safety. One study compared hikers in 3 different conditions; no backpack, a pack with 15% body weight and a pack with 30% body weight. Biomechanical analysis was performed blindly on the three groups and a significant reduction in forces on lower extremity joints (hip, knee, and ankle) was noted for all three groups when using poles compared to those not using poles.

Another study confirmed that trekking poles reduced the incidence of ankle fractures through improved balance and stability. Additional studies support the theory that trekking poles reduce exercise induced muscle soreness from hiking or walking steep terrain and another study found that while less energy is expended in the lower body muscles using poles, increase energy is used in the upper body; therefore, the net caloric expenditure is equal as it is simply transferred from the legs to the arms.

In conclusion, it is important to remember that trekking poles for hiking or distance walking are much more than a style statement. They are proven to be an invaluable tool for health, safety and wellness by reducing lower extremity joint stress, improving stability and balance, and enhancing efficiency for muscle recovery.

Sources: Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. The Complete Walker, by Colin Fletcher

Model: Andrea Molitoris, PT, DPT at Mackarey Physical Therapy

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopaedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

Total knee replacement surgery is one of the most commonly performed orthopedic surgeries in the U.S. for individuals older than 40. Given historical trends, these procedures are anticipated to increase in volume by an estimated 143% by 2050.

Knee replacement surgery is widely considered a safe and effective surgical option for patients with end-stage osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis of the knee. The surgery aims to maximize the quality of life for patients by reducing pain and improving joint functionality. Unfortunately, research estimates between 1 and 10 percent of patients may experience persistent pain, limited range of motion and loss of function after surgery. This rare but devastating outcome is thought to be associated with arthrofibrosis or scar tissue build-up around the joint which ultimately has a negative impact on an individual’s daily activities and affecting emotional well-being and satisfaction. Thankfully there are remediation treatment options to consider in this situation. One non-invasive, safe, and effective possibility is manipulation under anesthesia (MUA).

Manipulating the knee joint under anesthesia aims to forcefully release fibrous adhesions formed after surgery. It is considered a simple and effective medical procedure performed under general or regional anesthesia, ensuring complete muscle relaxation without any pain experienced. The procedure uses force to overcome adhesions in a controlled manner. While lying on their back, the patient's hip is flexed to a 90-degree angle, and the lower leg is used as a lever to bend the knee until a firm endpoint is reached. Force is also applied to the kneecap to free adhesions found there. These movements are repeated several times until the best range of joint motion is achieved.

Sam, a 44-year old mother and second-grade school teacher suffers from painful osteoarthritis. She underwent knee replacement surgery for both knees. However, 3 months after her surgery, she continued to experience intractable pain, swelling, and an inability to fully bend her knee. She was using a walker to assist her and could not tolerate long periods of standing. She struggled with basic daily activities and became increasingly despondent. Clinical evaluation showed that Sam was not able to bend either knee to 90 degrees. At this point, the healthcare team suggested Sam consider the MUA procedure to release the scar tissue to help move her recovery forward.

Over time, we know that adhesive tissue tends to increase in quantity and maturity. This leads to progressively worsening pain and loss of joint mobility. Literature suggests that earlier MUA intervention provides better outcomes and is more effective. Still, there is no clear consensus on the timing, and MUA may still be effective when performed later. Because clinical improvement after replacement surgery should occur between 6-12 weeks — orthopedic practices often apply a generic 90 by 90 rule of thumb. The rule signifies the ability to bend your knee to 90 degrees within 90 days after surgery. If unable to attain the 90 by 90 goal, MUA is often recommended. This is not a hard and fast rule, and each patient is individually assessed throughout the recovery period.

Not everyone will be a candidate for MUA, and there are risks involved. Since force is being applied to the joint during the procedure, there is a possibility of bone fracture. Patients with osteoporosis or any other bone-weakening illness might be cautioned against the procedure. Other risks include bleeding into the joint and wound rupture. It is also important to recognize that any procedure involving anesthesia is taxing on the body and carries additional risks. It is prudent to discuss all risks and benefits with your surgeon and healthcare team fully.

MUA intends to relieve pain and discomfort and help further increase the functional range of motion in the knee joint. Biomechanically we require a knee to flex or bend, ranging from 67 degrees for walking through to 105 degrees to rise from a low chair; and 115 degrees to squat or kneel. Immediately following the procedure, joint mobility is notably improved. Research studies have recorded an average increase in flexion of 29 degrees immediately after MUA, with continued improvements over time. Individual outcomes do vary. Current literature indicates having had two or more prior knee surgeries or injury to the joint, or a stiffer knee with less than a 70-degree bend 90 days after your replacement surgery, might yield less favorable outcomes.

Sam underwent her MUA 4 months after her initial knee replacement surgery. Physical therapy is started immediately following the MUA to ensure the best outcomes. During her initial evaluation less than 24 hours after the procedure, Sam could bend both knees by herself to 90-95 degrees, something she could not do before. Less than a month after her MUA, and with continued physical therapy, she reached a 115/120 degree bend. Sam had several risk factors; early-onset osteoarthritis, high body mass index (BMI) and previous knee surgeries. These factors complicate Sam's recovery and may have lead to her failure to attain the 90 by 90 goal. Still, she told me if given a choice again; she would make the same decision. Sam smiled and told me she no longer relies on her cane to walk, can walk up and down stairs almost normally and she is eager to start driving again.

The American poet Sheldon Silverstein wrote in his poem "Stop Thief!", "...Help me please. Someone went and stole my knees. I'd chase him down but I suspect my feet and legs just won't connect." Our knee forms such an integral part of daily life and activities— yet we seldom appreciate that it is one of our most stressed and complex joints, needing 10 muscles for movement and stability, and requires varying degrees of flexibility to get us through the day.

Next Monday, in part 2 of this article, we examine factors that might predispose a patient to scar tissue induced persistent pain and limited functionality after knee replacement surgery; and possible steps to avoid this.

This column is a monthly feature of “Health & Exercise Forum” in association with the students and faculty of Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine.

Author: Hendrik Marais, MD, MS

Hendrik Marais, MD, MS, received his Doctor of Medicine degree from Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine in 2015 and his Master of Science degree in Global Medicine from Keck School of Medicine at USC in 2019. He is passionate about creating positive and empowered patient health outcomes. He grew up in South Africa and currently calls Scranton, PA home – where he enjoys cycling, swimming, and discovering the beauty of NEPA. He is a member of the American Medical Association, American Public Health Association, and the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. He plans to pursue a clinical career in physiatry.

NEXT MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” Part II of III on Recovery From Knee Surgery

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles visit: https://mackareyphysicaltherapy.com/forum/

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine.