While I normally do not address the topic of shoveling snow until January, considering recent weather events, I thought it might be valuable to present it sooner. Much has been written about the dangers of snow shoveling for your heart. However, while not fatal, low back pain is the most common injury sustained while shoveling snow. Heart attacks are also more common following wet and heavy snow.

Snow shoveling can place excessive stress on the structures of the spine. When overloaded and overstressed, these structures fail to support the spine properly. The lower back is at great risk of injury when bending forward, twisting, lifting a load, and lifting a load with a long lever. When all these factors are combined simultaneously, as in snow shoveling, the lower back is destined to fail. Low back pain from muscle strain or a herniated disc is very common following excessive snow shoveling.

Sources: The Colorado Comprehensive Spine Institute; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Visit your doctor regularly and listen to your body.

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

Recently, two patients asked me when I thought it would be safe for them to return to their exercise programs after abdominal surgery. She stated that she was not sure how to properly and safely implement or return to her program.

This column will attempt to ensure a safe return to activity and exercise following general surgery such as gall bladder, appendix, hernia, etc. The post-operative patient has many questions: When is it safe to begin an exercise program? How do I begin? What is the best exercise? Which exercises are best? How do I know if the activity is too intense or not intense enough? Are there safe guidelines?

Before you begin, discuss your intention to exercise with your surgeon and primary care physician. Get medical clearance to make sure you can exercise safely. With the exception of short daily walks, don’t be disappointed if your surgeon requires you to wait at least until your 6 week post-op check-up to begin exercise.

While a 60 minute workout would be the long term goal, begin slowly at 15-20-30 minutes and add a few minutes each week. Make time to warm up and cool down.

Warm-up 5-10 minutes

Strength Training 10-15-20 minutes

Aerobic 10-15-20 minutes

Cool down 5-10 minutes

How to Monitor Your Exercise Program:

First, determine your resting heart rate by taking your HR (pulse) using your index finger on the thumb side of your wrist for 30 seconds and multiply it by two. 80 beats per minute is considered a normal HR but it varies. This is a good baseline to use as a goal to return to upon completion of your workout. For example, your HR may increase to 150 during exercise, but you want to return to your pre exercise HR (80) within 3-5 minutes after you complete the workout.

For those who are healthy, calculating your target heart rate (HR) is an easy and useful tool to monitor exercise intensity.

220 – Your Age = Maximum Heart Rate

EXAMPLE for a 45 year old: 220 – 45 = 175 beats per minute should not be exceeded during exercise.

For those concerned about calories expended during exercise.

NOTE: Keep the level at a light/moderate level for the first four to six weeks and advance to the moderate/heavy at week six. The Very Heavy Level may not be appropriate for 12 weeks post op is for those who have a reasonable fitness level and exercise 4-5 days per week.

Example of Data Found on Fitness Equipment

Remember, this is only accurate if you program your correct height, weight and age.

Level kCal/min MET

Light 2 - 4.9 1.6 – 3.9

Moderate 5 - 7.4 4 – 5.9

Heavy 7.5 - 9.9 6 - 7.9

Very Heavy 10 - 12.4 8 – 9.9

Always secure physician approval before engaging in an exercise program.

If the patient is on beta blockers (Atenolol, Bisoprolol, etc), it is important to use the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale (RPE) scale to determine safe exercise stress since exercise will not increase HR as expected:

0 - Nothing at all

1 - Very light

2 - Light

3 - Moderate

4 - Somewhat intense

5 - Intense (heavy)

6

7 - Very intense

8

9 - Very, very intense

10 - Maximum Intensity

NOTE: Keep the RPE at 2-3 the first 6 weeks post op and advance to level 3-4 at 8-12 weeks post op. Levels 5-6-7 are for those with a reasonable fitness level and exercise 4-5 days per week. The advanced levels should not be attained until 2-3 months of exercise and 3-4 months post op.

MEDICAL CONTRIBUTOR: Timothy Farrell, MD, is a general surgeon at GCMC.

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

Fall has arrived in NEPA and walking is a great way to enjoy the fall foliage. Moreover, a new study has found that walking can reduce lower back pain. Researchers in Australia followed more than 700 adults who had a recent onset of lower back pain (and were able to bear full weight without associated leg symptoms) and enrolled them in a walking program under the supervision of a physical therapist. One group walked for 30 minutes, 3-5 times per week and the control group remained inactive. Both groups were followed for more than three years and discovered that the inactive control group was twice as likely to suffer from repeated flare-ups of lower back pain when compared to the walking group.

It is good news for those who enjoy walking, however, for many who have not maintained an active lifestyle or have health issues, it is challenging to know where to begin. Also, beginning without a good plan can lead to injury and leave you discouraged. For example, those overweight and de-conditioned should not start a walking program too aggressively. Walking at a fast pace and long distance without gradually weaning yourself into it will most likely lead to problems.

There is probably nothing more natural to human beings than walking. Ever since Australopithecus, an early hominin (human ancestor) who evolved in Southern and Eastern Africa between 4 and 2 million years ago, our ancestors took their first steps as committed bipeds. With free hands, humans advanced in hunting, gathering, making tools etc. while modern man uses walking as, not only a form of locomotion, but also as a form of exercise and fitness. It is natural, easy and free...no equipment or fitness club membership required!

Walking to reduce or control lower back pain is only one of many important reasons to begin a program. According to the American Heart Association, walking as little as 30 minutes a day can provide the following benefits:

Anything is better than nothing! However, for most healthy adults, the Department of Health and Human Services recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous aerobic activity. The guidelines suggest that you spread out this exercise during the course of a week. Also aim to do strength training exercises of all major muscle groups at least two times a week.

As a general goal, aim for at least 30 minutes of physical activity a day. If you can't set aside that much time, try several short sessions of activity throughout the day (3 ten or 2 fifteen-minute sessions). Even small amounts of physical activity are helpful, and accumulated activity throughout the day adds up to provide health benefit.

Remember it's OK to start slowly — especially if you haven't been exercising regularly. You might start with five minutes a day the first week, and then increase your time by five minutes each week until you reach at least 30 minutes.

For even more health benefits, aim for at least 60 minutes of physical activity most days of the week. Once you are ready for a challenge, add hills, increase speed and distance.

Keeping a record of how many steps you take, the distance you walk and how long it takes can help you see where you started from and serve as a source of inspiration. Record these numbers in a walking journal or log them in a spreadsheet or a physical activity app. Another option is to use an electronic device such as a smart watch, pedometer or fitness tracker to calculate steps and distance.

Make walking part of your daily routine. Pick a time that works best for you. Some prefer early morning, others lunchtime or after work. Enter it in your smart phone with a reminder and get to it!

Studies show that compliance with an exercise program is significantly improved when an exercise buddy is part of the equation. It is hard to let someone down or break plans when you commit to someone. Keep in mind that your exercise buddy can also include your dog!

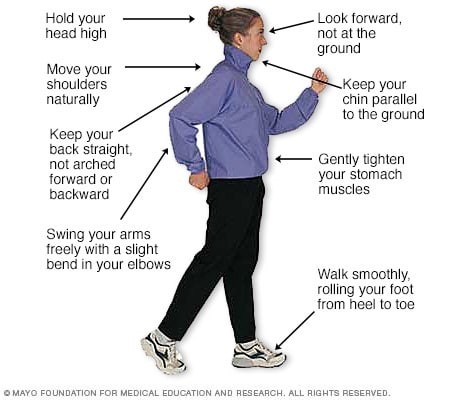

Like everything, there is a right way of doing something, even walking. For efficiency and safety, walking with proper stride is important. A fitness stride requires good posture and purposeful movements. Ideally, here's how you'll look when you're walking:

Sources : Sapiens.org; WebMD; Mayo Clinic, “Health & Science New”

Visit your doctor regularly and listen to your body

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!

Have you ever noticed high level athletes warming up before a game or competition walking or running backwards? You may also see fitness enthusiasts in gyms emulating these athletes to improve their fitness or performance. I found the concept of backward walking, (also called retro walking) interesting and decided to research the topic for more information and validation. Walking backward does have many therapeutic benefits, however, before you attempt this activity on a treadmill or elliptical, please consult your physician and physical therapist and have a spotter nearby.

At a recent meeting of The American College of Sports Medicine, several studies were presented on the topic of backward waking. Most of the research was conducted while moving backward on a treadmill and an elliptical machine. When comparing two groups recovering from knee injuries, the backward motion group showed significant improvement in strength in the quadriceps (front thigh) and hamstring (back thigh) muscles when compared to the traditional forward walking group. Furthermore, the muscles of the front (tibialis anterior) and back (gastro/achilles) of the shin/ankle also demonstrated an increase in strength and endurance with backward walking. One explanation is that forward motion is routine in daily living that it has become very efficient and does not tax or stress the muscles the body. While this efficiency prevents fatigue in daily activities, it may not stress the muscles enough to gain strength as quickly as an unfamiliar exercise.

Due in great part to the increased strain of performing an unfamiliar exercise, backward walking on a treadmill or backward pedaling on an elliptical, offered a greater cardiovascular benefit and caloric expenditure than forward motion at all levels. Specifically, walking backward on a treadmill at 2.5 mph at grades of 5% - 10% has been found to significantly increase cardiovascular endurance than walking forward under the same conditions. This knowledge is useful for healthy individuals in need of greater cardio exercise. However, it may also serve as a precaution for those with cardio problems and should consult their physician prior to engaging in this activity.

A recent study in the International Journal of Obesity, found that those who performed new activities or increased the intensity of an activity, even if for a short duration (interval training) expended more energy and burned more calories than those who worked out at the same pace consistently for a longer duration. Moreover, when engaging in a new activity such as backward walking, even more calories were burned. This phenomenon may be due to the fact that routine activities such as forward walking are performed more efficiently and easily.

We challenge our body when we inefficiently perform a new motor skill such as backward walking and burn more calories. In other words, if you want to burn more calories without exercising for longer periods of time, than try a new activity and engage in higher intensity, intermittently, for part of the time. For example, walk backward on the treadmill for 30 minutes at 2.5 mph, but do so at a 5 – 10% incline for 1-2 minutes every 5 minutes.

Some studies show that using other muscle groups by performing different exercises not only prevents boredom, but also protects your muscles and tendons from overuse and joints from wear and tear. Specifically, the knee joint and the patella joint (the joint where the knee cap glides on the knee), benefits from backward walking due to less stress and compression forces on the joint. The thigh and ankle/foot muscles benefit from using a different form of contraction while lengthening the muscle. Some authors propose that this may also prevent strains and pulls and may be valuable to strengthen those with a history of shin splints and flat feet (pronation).

Mixing up your program prevents boredom. As a rule, those willing to change their exercise routine are more compliant and continue to exercise longer than those stuck in the same routine. A new challenge to improve distance, speed, and resistance while exercising in a different direction will be refreshing to your program.

Prevention of falls by improvement in balance and coordination has received a great deal of attention in the past few years. This is not only valuable to the athlete but may be even more important to those over 50. With age, balance centers are slow to react to changes in inclination, elevation, rotation and lateral movements. This slow reaction time leads to falls that may cause fractures, head injuries and more. Working on this problem by challenging the vestibular and balance centers before it is seriously compromised is important and backward walking is one way for this to be effectively accomplished.

Visit your doctor regularly and listen to your body.

EVERY MONDAY – Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” via Blog

EVERY SUNDAY in "The Sunday Times" - Read Dr. Paul J. Mackarey “Health & Exercise Forum!” in hard copy

This article is not intended as a substitute for medical treatment. If you have questions related to your medical condition, please contact your family physician. For further inquires related to this topic email: drpmackarey@msn.com

Paul J. Mackarey PT, DHSc, OCS is a Doctor in Health Sciences specializing in orthopedic and sports physical therapy in Scranton and Clarks Summit. Dr. Mackarey is in private practice and is an associate professor of clinical medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine. For all of Dr. Mackarey's articles, visit our exercise forum!